Landscapes – Native Scottish Trees

Native tree species are those which arrived naturally in Scotland without direct human assistance as far as we can tell. Most of our native tree and shrub species colonised Scotland after the last Ice Age (which ended roughly 9,000 years ago), with seeds dispersed by wind, water, and animals. The Cateran Trail’s most common native trees include Scots Pine, Birch (Downy and Silver), Oak (Pedunculate and Sessile), Willow (various species) and Rowan.

Scots Pine

The Scots Pine – or Pinus Sylvestris – is Scotland’s national tree. It was prevalent in the once extensive Caledonian pine forests, and is the only timber-producing conifer that’s native to Scotland. It is known as a pioneer species, due to its ability to regenerate and thrive in poor soils. You can find the Scots pine further afield too, it’s extensively planted in Europe and beyond. Scots Pine timber is known as ‘red deal’, and is strong and easy to work with. It may not be naturally durable, but it takes preservatives well.

Birch

Both Silver Birch and Downey Birch are widespread around the Cateran Trail, with silver birch occurring principally on the well-drained, drier soils and downy birch preferring the wetter locations. They grow as largely monospecific stands, or birchwoods and also within other forest types, such as pine and oak woods. Before much of Scotland was deforested of by humans, when much larger areas of Scots pine and oak forests flourished, it is likely that birch was less common than it is today.

Oak

The Oak tree once formed a third of all tree cover in Britain. Its wood is very dense which creates great strength and hardness and means that it has always had many practical uses from ship building to making timber frames for buildings. Oaks are keystone species, which means they play a unique and crucial role in supporting lots of other different organisms in an ecosystem from birds to worms and bacteria. Without keystone species, the ecosystem would be dramatically different or cease to exist altogether.

Willow

Willows, also called sallows, and osiers are found primarily on moist soils. All species, of which there are 400), have abundant watery bark sap, usually pliant, tough wood, slender branches, and large, fibrous roots. The roots are remarkable for their toughness, size, and tenacity to live, and roots readily sprout from aerial parts of the plant. Almost all willows take root very readily from cuttings or where broken branches lie on the ground. They are often planted on the borders of streams so their interlacing roots may protect the bank against the action of the water.

Rowan

The mystical, distinctive rowan tree is found higher up in the mountains than any other native tree. Its botanical name is Sorbus aucuparia and it’s often called the ‘mountain ash’, although has no relation to the ash tree. In the past, superstitious residents planted rowan trees outside houses and in churchyards to ward off witches. And more recently, this favourable tree came second to the Scots pine in the running for Scotland’s national tree.

Download List

- Story – Native Scottish Trees

- Lesson Plans

- Worksheet

- Look

- Did You Know?

- Test Your Knowledge

- Read The 100 Objects Booklet

Landscapes – Highland Boundary Fault

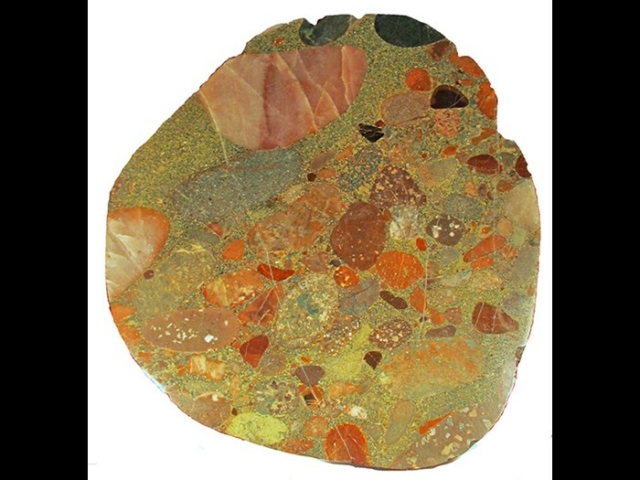

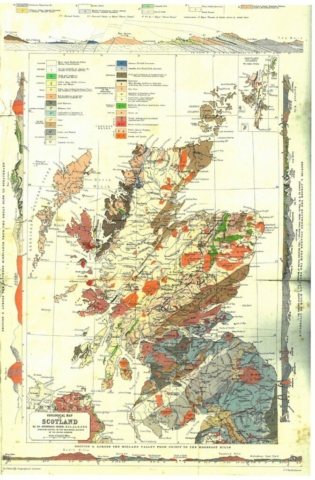

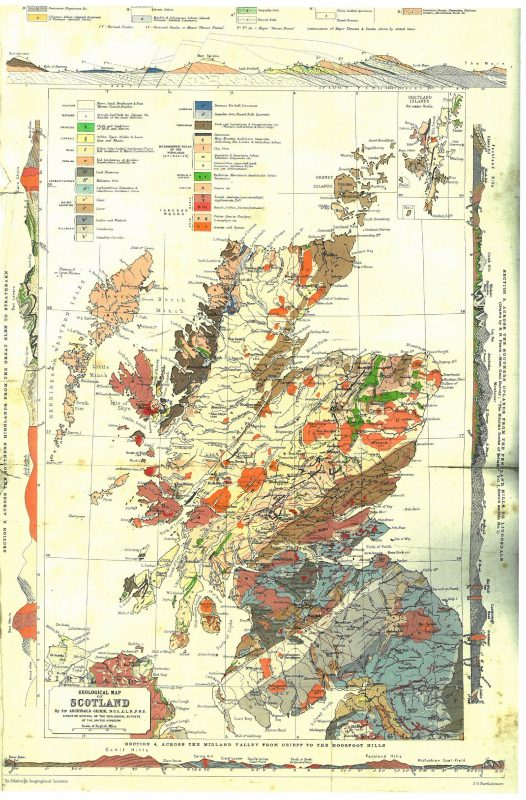

The Highland Boundary Fault is a geological fault line that runs across Scotland from Arran in the west to Stonehaven in the east.

Along the way, it goes through Blairgowrie, Alyth and Kirriemuir.

The Boundary Fault’s heyday was around 400 million years ago, during collisions of ancient continents. This was a time when both the mountains in much of the Highlands rose and the Central Lowlands sank, forming a huge valley across the middle of the Scottish mainland.

Reekie Linn near the Cateran Trail is a waterfall formed on the Highland Boundary fault where the hard metamorphic rocks of the Highlands give way to the softer sedimentary rocks of Strathmore

The falls were created when the hard volcanic rock gives way to the much softer sandstone. At the boundary of these rocks is the waterfall. The hard volcanic rocks resist erosion whilst the softer sandstone will gradually erode. The falls have created a plunge pool at their base 36 metres deep. The erosion of the sandstone will eventually cause the falls to undermine themselves and collapse. This continuous erosion / undermining / collapse over thousands of years has created the spectacular gorge downstream as the falls have migrated upstream.

The Highland Boundary Fault remains not only the most important geological division in Scotland but for a long time from the late middle ages, it was a great cultural boundary as well because it determined how people settled the land and what they could do with it.

The hard rocks north of the fault line made it difficult to grow crops, whereas the softer sandstone south of fault line created some of the most fertile soils in Scotland supporting a wide range of agricultural activities. The different way the land was able to be used meant that in those times people structured their society differently too. What is called a feudal system of land ownership was more common south of the faultline where you could grow lots of food. Here, land was granted to people for service. It started at the top with the king granting his land to a baron for soldiers all the way down to a peasant getting land to grow crops. North of the faultline, where it was harder to grow crops, the clan system was more dominant. This more warrior like social structure helped people to survive in a harsh environment. For a large part of Scotland’s history it also marked a distinct change linguistically from English to Gaelic.

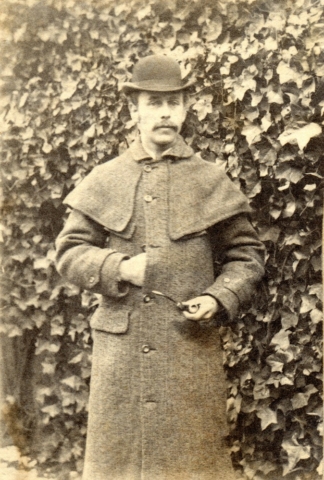

(Photo: courtesy of Christopher Dingwall)

Download List

Landscapes – Drove Roads

Cattle drovers, people who drive cattle to market, were regarded as important members of the Highland community. The upland soils are ill-suited to growing crops so cattle-rearing was a vital part of the Highlander’s life and economy.

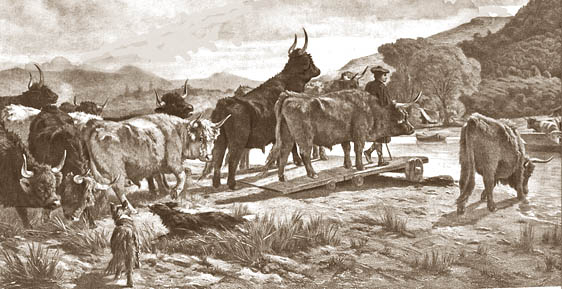

Hardy Highland cattle were gathered from settlements and farmsteads across the northern glens and driven south along traditional routes (see map in ‘Look’ section) to ‘Trysts’ – meaning fair or market – where they could be fattened and sold for slaughter. Many of the routes would have followed specific topographies that the cattle could manage.

The cattle themselves were the forerunners of today’s Highland cattle. They were much smaller than most breeds today, probably not weighing much more than 254 kg’s, and were, and still are, the hardiest of breeds and easy to handle. Until red/brown variants were exported from Glen Lyon in the mid 19th century, they were black. The gene for the red/brown colour proved to be dominant and this is now the colour of most of the breed in various shades.

Scottish droving grew to a huge scale in the 18th and 19th centuries following the Union between Scotland and England in 1707 when it became easier to trade across the border. The Napoleonic Wars in the early 19th century created an exceptionally high demand because it was the custom to give a daily ration of salt beef to every soldier and there were an enormous number of men under arms in the British army and navy at that time.

All drove roads led to the Trysts. Cattle from the North East of Scotland, Morayshire, Aberdeenshire, and Angus, passed through Alyth and Blairgowrie, whereas those from further north and west converged on Kirkmichael on their way south towards Dunkeld and the great cattle fairs at Crieff and Falkirk where the big sales took place on the first Tuesday of August, September and October.

Two hundred acres of land were needed to hold the 150,000 cattle, sheep & horses that streamed each market-day into Falkirk from all corners of Scotland. As many as 2,000 drovers, with their dogs and ponies, would sleep in the open and meet with hundreds of buyers from all over Britain. One observer remarked: “Certainly Great Britain, perhaps even the whole world, does not afford a parallel.”

A drover’s day was a long one. At about 8.00 am they would rise and make a simple breakfast of oats, either boiled to make porridge or cold and uncooked mixed with a little water. The whole might be washed down with whisky. Oats, whisky, and perhaps some onions were their basic diet. Occasionally, they might draw blood from some cattle and mix it with oatmeal to make “black pudding.”

The herd would move off on a broad front of several strings of cattle of four or five beasts abreast, moving perhaps 16-20 km or less a day. The cattle had to be managed skillfully to avoid wearing them down or damaging their hooves, and the drover had to know where he could obtain enough grazing along the way. At the days end, the cattle might stop near a rough inn where some shelter could be obtained, or perhaps the drovers had to sleep out on the open hill in all weathers with only their tartan, woven cloth, called their plaid, to protect them. At night someone always had to guard the herd to prevent cattle straying or rievers stealing them. It was a hard and, at times, dangerous life, but the Highlanders, with their warlike, ‘rieving’ (cattle thieving) past, and hardy upbringing were well suited to it.

Listing the necessary attributes of a drover, A.R.B. Haldane, who made a special study of the drover, wrote that they had to have extensive and intimate knowledge of the country and cattle, endurance and an ability to face great hardship, enterprise and good judgment and honesty and reliability for the responsible work that was entrusted to him.

In addition to that, they were also often skilled on the bagpipes or learned in other aspects of their Gaelic culture and at the Trysts during the evenings around the fire,the drovers would tell stories linked to their journeys, folk and fairy stories, cow and horse tales, legends explaining ancient features in the landscape, and stories of place names spanning centuries. Many of these stories are now forgotten or are only remembered by a handful of local people who recall living and working on the land.

The peace, after the battle of Waterloo in 1815 finished the Napoleonic wars, meant the shrinking navy needed less beef but other changes were even more important. The first half of the nineteenth century saw a revolution in agriculture. Enclosed systems of fields replaced open common grazing and large, fatter cattle were bred and raised ready for market. More importantly, by the 1830s, faster steamships were being built and farmers in the lowlands and elsewhere started to ship cattle directly to the southern markets instead of by the long arduous overland droves. Then, once railways were established by the 1880, this provided an even swifter and more reliable means of transporting cattle and other agricultural products to market. By then, moreover, the cattle had been carefully bred and were not hardy enough to take the long road anyway. By 1900 the great trysts were all but dead.

(Photo: Thought to be a painting of a Drove through Callander, Perthshire in the 1870’s on the way to the autumn Falkirk Tryst, artist unknown)

Download List

Places – The Bannerfield, Kirkmichael

Marching south from Braemar, the Earl of Mar raised the standard (or banner) here during the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion to gather support for the exiled Stuart King James, known as the Old Pretender.

James father, King James VII of Scotland (James II of England) had been overthrown by William of Orange during the revolt of 1688-1689 (often called the Glorious Revolution). This ended the Catholic line of the Stuart dynasty and established the protestant succession of the House of Hanover.

However, there were still many in Scotland and England who wished to return the Stuarts to the throne. Supporters of the Stuarts were called Jacobites (taken from the Latin form (Jacobus) of the name James). The Jacobites usually attempted to retake the throne for the House of Stuart during time of political turmoil and there were attempts in 1708, 1719 and 1745 but the best chance of success came in 1715.

After gathering more men at Kirkmichael, Mar marched into Perth (which had been captured two weeks previously) with an army of 5000 and support of many powerful landowners. Here the army grew and by October, Mar had well over 7000 men under his command. At the time, the Government Army in Scotland at the time totaled only around 3500 men but it was led by John Campbell, the Duke of Argyll who was an experience soldier. Both army’s met at Sheriffmuir on the 13th of November. The battle was indecisive but Mar abandoned of his short term strategic aim to cross the Forth and instead retreated back to Perth. The English Jacobites had been crushed at the battle of Preston and the Government army was steadily increasing.

James Francis finally joined Mar in Perth in January but the fight was effectively over. Support from France had not materialised and desertions had depleted the Jacobite force. By February James was on his way back to France, along with Mar and a few high-ranking Jacobites.

Estates were fortified and cities and towns throughout Scotland were heavily garrisoned. Many of the Scottish Jacobite leaders were allowed to escape into exile to avoid charges of high treason. However, those captured at Preston and tried in England were not so lucky and many faced jail, transportation or execution.

In more recent times, the Bannerfield has become the venue for the annual Strathardle Highland Gathering, now celebrating its 136th year.

(Photo: Aerial Photo of Kirkmichael with the Bannerfield in the top right hand corner, courtesy of Perth & Kinross Heritage Trust)

Download List

Places – Oakbank Mill

The waters of the River Ericht at Blairgowrie once drove a remarkable series of 14 spinning mills. Originally working with flax, but later mostly spinning jute, these enterprises brought employment and prosperity to the area.

Oakbank Mill was one of these mills. It was built by James Grimond and was the first mill in Scotland to spin jute successfully. The jute was softened with whale oil; cut into lengths, heckled, where the fibres were drawn into straight, tangle-free lengths; spun into 3-lb yarn; and mixed with tow for the weft of osnaburg (a coarse, plain fabric) and hessian sheeting. The jute was a fine fibre and this tradition of producing fine jute threads was carried on in Blairgowrie into the 1940s.

The mills of Blairgowrie were built by a series of entrepreneurs eager to take advantage of the business opportunities offered by the mechanisation of the textile industry. The earliest known spinning machinery was installed in a lint mill in Rattray (which later grew into the Erichtside works) in about 1796. This was followed by the construction of a new purpose built mill in Blairgowrie (the Meikle Mill) just above the Bridge of Blair in 1798. Mill construction after this was infrequent until about 1830 by which time a new generation of more sophisticated and reliable spinning machinery had become available. Some seven new mills were then built between 1830 and 1845. As the power from the river was however limited and not really sufficient to drive heavy power looms the Ericht mills concentrated on spinning thread. Machine weaving was carried out in the large Dundee mills which were powered by steam engines.

The jute industry began to decline at the start of the 20th Century, mainly due to competition from mills in India where labour costs were much lower. The Ericht mills became progressively uneconomic and started to close. Despite minor booms during the two world wars and experiments such as spinning artificial fibres, the last working mills on the Ericht were forced to shut down in 1979.

(Photo: Oakbank Mill, courtesy of Clare Cooper)

Download List

- Story – Oakbank Mill

- Lesson Plan

- Work Sheet

- Look

- Did You Know?

- Test Your Knowledge

- Read The 100 Objects Booklet

Places – Barry Hill Fort

Barry Hill is one of the best preserved examples of an enclosed hilltop settlement in Scotland. Although Barry Hillfort has not yet been excavated, similar monuments have been found to date from the late prehistoric period, around 3,000 years ago.

During this period, people began defining and enclosing their settlements. This was a time of climatic deterioration. As conditions became colder and wetter, cultivation of higher altitude land became less sustainable and people began to move into lower lying areas. This contraction of viable land is one suggestion late prehistoric people felt the need to define and protect the land where they lived. Hillforts are a very distinct form of enclosed settlement that emerged during this period of change and there are few examples more dramatic than Barry Hill.

Hillforts are highly visible, enclosed by a single or a series of defensive lines or ditches and stone, timber or banked-earth ramparts.

We tend to think of them chiefly as strongholds, defensive bolts or like modern towns where people made, bought & sold goods and they certainly would have played a key role in prehistoric society, perhaps displaying the power and control of their occupants over the surrounding land and resources. They could also have been important meeting places and played a symbolic role for example being used seasonally as centres for religious rituals.

Myths and legends often develop around such sites and Barry Hill is no exception with its links to the legend of Vanora, the Scottish name for King Arthur’s Queen Guinevere.

Often archaeological evidence finds multiple phases of building, defences and occupation activity, sometimes with long spans of inactivity in between.

Barry Hill has never been excavated, but from detailed topographic survey (a map of the contours of the ground and existing features on the surface of the earth or slightly above or below the earth’s surface) we can identify that Barry Hill has several phases of construction including a later massive stone rampart (now reduced to rubble) enclosing the summit of the hill and an earlier series of stone and earth ramparts which take in a much larger area. Beyond the main occupation phases there is also later disturbance by quarrying for millstone in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Story of Vanora

The legend of Vanora has her as the queen of Arthur, a 6th century king of Strathclyde. Before leaving to go on a pilgrimage to Rome, Arthur appointed his nephew Modred to act as his regent and rule in his place. No sooner had Arthur left the country than Modred seized the throne and seduced his aunt, Vanora. Soon they were ruling as man and wife with Pictish troops to enforce their rule. It was only a matter of time before Arthur found out what had happened and he immediately headed home to raise his followers and have his revenge. The battle where Arthur and Modred met is said to have been at Camlaan, near Carlisle, however, new historical research also places the battle of Camlann around the Hill

of Alyth. True to the old myths Arthur was victorious but in killing Modred he sustained a mortal wound himself. Soon he died and with him went any faint hope Vanora might have treasured for merciful treatment. First imprisoned at Barry Hill, next door to Alyth, she was found guilty of treason and adultery and torn to pieces by a pack of wild dogs. Her grave mound is still marked in the Churchyard of nearby Meigle and the grisly scene of her death is said to be portrayed on the great Vanora Stone, part of one of the most important collections of Pictish symbols stones in the world found around her grave mound and now housed in Meigle’s famous Pictish Stone Museum.

(Photo: An Aerial View of Barry Hill showing the ramparts, photo courtesy of Perth & Kinross Heritage Trust)

Download List

People – The Caterans

‘Cateran’ derives from the Gaelic word ceatharn meaning ‘warrior’, but usually one that is lightly armed. The term was originally given to a band of fighting men of a Scottish Highland clan but in the lowlands, came to be associated with Highland cattle raiding. The earliest documentary evidence we have for Cateran raids is in the mid- to late- 13th century.

But what gave rise to the cattle-raiding Caterans and why did they attack places like Glenshee, Glen Isla and Strathardle? One Scottish historian has suggested that given the dates of the first recorded raids, the aftermath of the wars with England, plague and environmental factors such as climate change led to fall in population and colder and wetter weather. This led to greater difficulty in raising crops in an area (i.e. the Highlands) that was always marginal and so two alternative ways of making a living – herding cattle and raiding cattle became more prevalent.

Another historian suggests that cattle raiding is purely a practice of inter-tribal activity that he believes had been part of clan life for many centuries and may have had its origins as far back as the Iron Age.

Many stories have been handed down over the centuries about the Caterans, some of which can be found in Stuart McHardy’s book ‘The School of the Moon.’ Here’s one about Chalmers of Morganstoune:

During the 18th century, a man named Chalmers, who lived at Morganstoune (close to Brideg of Cally), was prepared to protect his property fiercely from the Caterans who plotted to murder him in his sleep. While out tending his cattle, Chalmers spotted some Caterans lying in wait. Pretending not having seen them, he went about the rest of his business, but that night stayed up to beat them at their own game. Eventually, a Cateran stealthily tried to enter the house and was killed by Chalmers, who then killed a second Cateran. The surviving Caterans crept away and never troubled Chalmers again.

(Photo: A Cateran in Glenshee by Kevin Greig, staneswinames.org, an original artwork commissioned for the Exhibition ‘A Story of the Cateran Trail in 100 Objects’, Alyth Museum 2017)

Download List

People – James Sandy

James Sandy was born in Alyth in 1766. Crippled in both legs from an early age as a result of two accidents, he nevertheless soon displayed remarkable talents for inventing all sorts of different kinds of objects which he made from a circular bed he had created with raised sides which allowed him to use turning lathes, table vices and tools.

His genius for practical mechanics was legendary. He was skilled in all sorts of turning, and constructed several very curious lathes, as well as clocks and musical instruments of every description, admired for the sweetness of their tone, as well as their beauty. He excelled too in the construction of optical instruments, and made some reflecting telescopes, the specula of which were considered to be as good as any produced by even the most eminent London fabricators.

He suggested some important improvements in the machinery for spinning flax; and was the inventor of a special type of wooden-hinged snuff box with a concealed hinge which did not get clogged with grains of snuff and when the box closed, was airtight. Generally called Laurencekirk boxes, some were purchased and sent as presents to the royal family. To his other endowments, he added an accurate knowledge of drawing and engraving, and in both these arts produced work that was considered of the highest excellence.

His curiosity, which was unbounded, prompted him to hatch different kinds of bird’s eggs by the natural warmth of his body, and he afterwards reared the motley brood with all the tenderness of a parent; so that, on visiting him, it was not unusual to see various singing birds perched on his head, and warbling the artificial notes he had taught them.

For upwards of fifty years he only left his bed three times, and on these occasions his house was either inundated with water or threatened with danger from fire. Nevertheless, he was a remarkable example of someone who despite great difficulties managed to use his ingenuity and industry to create a high degree of independence for himself.

Naturally possessed of a good constitution, and with an active and cheerful character, his house was the general coffee room of the village, where all the affairs of the world were discussed.

His grave lies in the Alyth Arches graveyard.

(Photo: Mauchlineware Box, courtesy Perth Museum & Art Gallery)

Download List

People – Belle & Sheila Stewart

Belle Stewart and her daughter Sheila were Scottish traditional singers and storytellers.

Their roots were in the Scottish Highland Traveller community, known in Scottish Gaelic as the “Ceardannan” (the Craftsmen) or “luchdsiubhail” (people of travel).

This community has a long history in Scotland going back, at least in record, to the 12th century as a form of employment and they share a similar heritage, although are distinct from, the Irish Travellers.

Highland Travellers are closely tied to the Scottish Highlands, and many traveller families carry clan names like Macfie, Stewart, Macdonals, Cameron, Williamson and Macmillan.

They often followed a nomadic lifestyle; passing from village to village, pitching their bow-tents on rough ground on the edge of the village and earning money there as tinsmiths, hawkers, horse dealers and pearl fishermen. Many found seasonal employment on farms, e.g. at the berry picking or during harvest.

Belle and Sheila were both born in the Blairgowrie area, Belle in 1906 in a bow-tent by the side of the River Tay at Caputh and Sheila in 1937 in a stable behind the the Angus Hotel in Blairgowrie after and argument between her mother and grandmother had rendered her parents homeless.

Their family was accustomed to the Traveller way of life where they survived through hawking, besom making, berry picking, tattie howking and flax harvesting. Sheila was adept at pearl fishing, as her grandfather had been, and in latter years she was happy to show the glass bottomed container used for seeing into the water to select the right fresh water mussel that could hide a treasured pearl.

It is generally agreed by folklorists that despite the deep rooted prejudice this community faced, the Scottish Travelling folk were considered to be amongst our finest oral tradition bearers, be it of song or tale, and whilst the kind of life that Belle and Sheila knew has now more or less died out, the way their culture nurtured creativity and valued traditions has had a huge influence on the ballad singing tradition of Scotland.

This rich cultural environment and the Stewart family’s own artistry ensured that Belle and Sheila became world famous for their songs and tales from the Perthshire berry fields – music and stories that we are still able to enjoy today.

(photo: Berry Picking in Strathmore, 1933, courtesy of the Laing Photographic Collection)