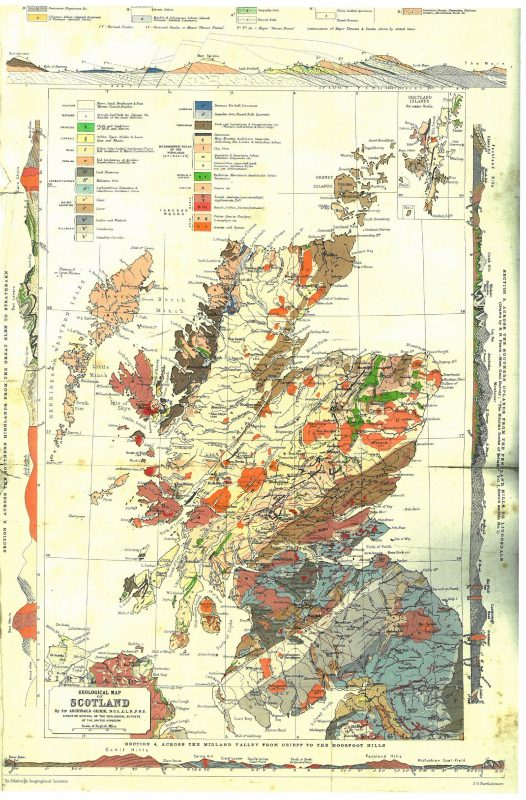

The Highland Boundary Fault is a geological fault line that runs across Scotland from Arran in the west to Stonehaven in the east.

Along the way, it goes through Blairgowrie, Alyth and Kirriemuir.

The Boundary Fault’s heyday was around 400 million years ago, during collisions of ancient continents. This was a time when both the mountains in much of the Highlands rose and the Central Lowlands sank, forming a huge valley across the middle of the Scottish mainland.

Reekie Linn near the Cateran Trail is a waterfall formed on the Highland Boundary fault where the hard metamorphic rocks of the Highlands give way to the softer sedimentary rocks of Strathmore

The falls were created when the hard volcanic rock gives way to the much softer sandstone. At the boundary of these rocks is the waterfall. The hard volcanic rocks resist erosion whilst the softer sandstone will gradually erode. The falls have created a plunge pool at their base 36 metres deep. The erosion of the sandstone will eventually cause the falls to undermine themselves and collapse. This continuous erosion / undermining / collapse over thousands of years has created the spectacular gorge downstream as the falls have migrated upstream.

The Highland Boundary Fault remains not only the most important geological division in Scotland but for a long time from the late middle ages, it was a great cultural boundary as well because it determined how people settled the land and what they could do with it.

The hard rocks north of the fault line made it difficult to grow crops, whereas the softer sandstone south of fault line created some of the most fertile soils in Scotland supporting a wide range of agricultural activities. The different way the land was able to be used meant that in those times people structured their society differently too. What is called a feudal system of land ownership was more common south of the faultline where you could grow lots of food. Here, land was granted to people for service. It started at the top with the king granting his land to a baron for soldiers all the way down to a peasant getting land to grow crops. North of the faultline, where it was harder to grow crops, the clan system was more dominant. This more warrior like social structure helped people to survive in a harsh environment. For a large part of Scotland’s history it also marked a distinct change linguistically from English to Gaelic.

(Photo: courtesy of Christopher Dingwall)